|

I started my blog here but quickly realized that the design of the site made it difficult both to follow the story the blog tells and to choose specific posts based on one's interests. For these reasons, I have moved this blog to learningthatmatters.substack.com// Please check out that blog to follow my adventures in course design and the intricacies of how one might ungrade, incorporate AI, and integrate all the important moves that we recommend in Learning That Matters. As I build and teach this course I will discuss in detail, often with additional attached examples:

0 Comments

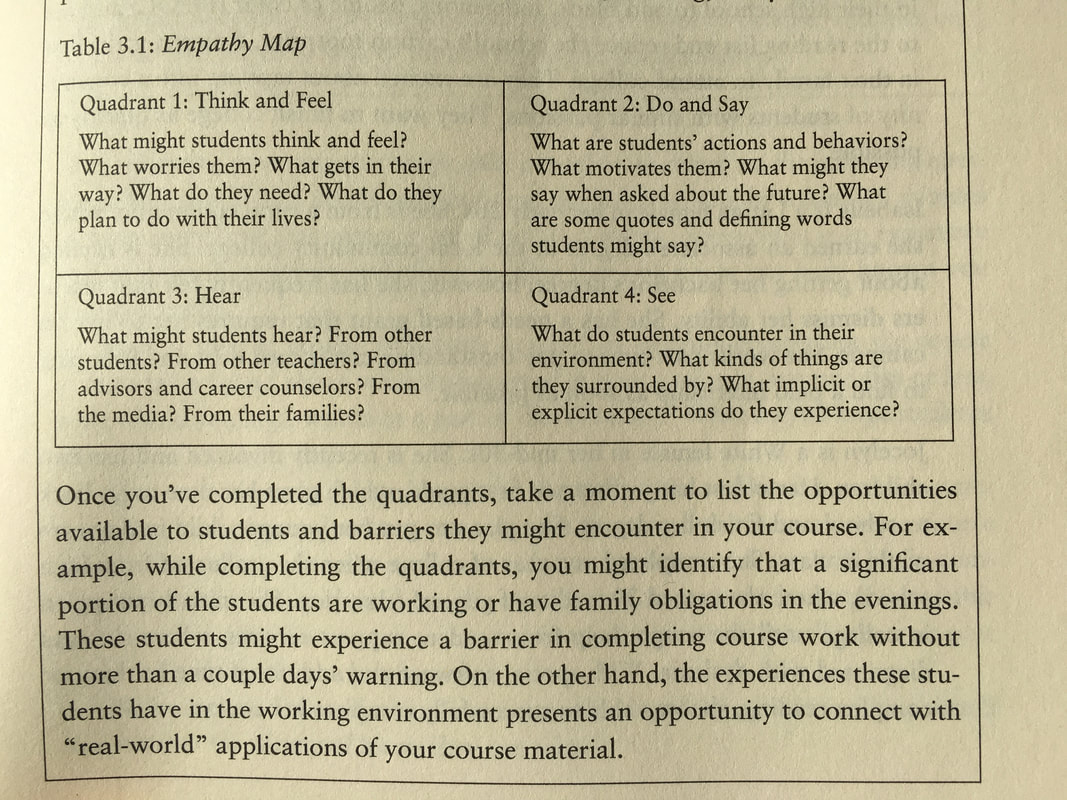

In the book we recommend using a combination of “Design Thinking” and “Backward Design.” More recently we came across the concept of “Liberatory Design” which is a similar process. Often, we create courses with a focus on the curriculum, but these methods begin with a focus on the learners. On pp. 36-37 we describe an activity to help articulate student perspectives called an “empathy map," and you can view that above.

Like most college professors, I do not know ahead of time who will be in my course, and this can be problematic because I want to tailor the courses as much as possible to the students in it rather than designing it for any random group of students. But here's my empathy map based on other first-year education courses I have taught recently and the demographics where I teach. The vast majority of my students will be 17-19 years old, female, and white but based on our student population, there is a good chance that quite a few will be first generation college students, LGBTQ, or neurodiverse. All or nearly all live on campus (required) and quite a few will have a part-time job. Most are planning to become P-12 teachers, primarily elementary teachers. They have enrolled in my course because it is the first course in a required sequence, but most will be genuinely interested, bright, and solid writers. They may still be suffering from the pandemic malaise I have witnessed in our incoming students the past two years. As this will be the first semester of college for the majority, they may believe that “success” in the course would mean getting an “A.”

Opportunities: freedom, the chance to meet new people and get out of their “bubble,” the chance to shed some aspects of who they were and start fresh Barriers: fears, fears, fears, and exhaustion and overwhelm But while the newness of everything can be a barrier, because this is the very first semester, they don’t have as many fixed ideas about how college is “supposed” to be and hopefully I can help them get off on the right foot and set them up for success. Composite personas As you can see above, we have a tendency to focus on the average student, the ones we’ve seen before, the ones that most closely fit our demographics. But designing a course for them alone would keep me from planning for the diversity, equity, and inclusion I value. Until I meet the students in my class and understand the many strengths and talents each brings, I am going to create a few “composite personas” to help me. These cannot be a substitute for actual humans but they can help make my planning more human-centered and inclusive of a broader range of perspectives and experiences. The following composites are based on institutional data and personal experience. Sasha is an 18-year-old African American female. She works part-time at our cafeteria. She had hoped more of the student body would be black, but at least she has found a supportive community through a friend who is a year ahead of her. She has a younger sister with severe physical impairments and so she has a passion for working with similar students in the future. JJ is a 20-year-old gay white male who took a couple of gap years before starting college. He has wanted to be a high school history English teacher for as long as he can remember but is now afraid that teaching might be a difficult profession for him given his devotion to diversity, equity, and inclusion and knowing that teachers have lost their jobs for mere mentions of anything related to LGBTQ+ individuals. Jackie is a 17-year-old white female who self-identifies as autistic. She took a lot of AP and dual-enrollment courses and so is starting her college career a bit younger than most. Other students are sometimes hesitant to work with her because she sometimes monopolizes conversations. Despite a history of high grades, she has never felt like school was a good fit for her, and finding workarounds has been exhausting. She has unusually interesting and innovative ideas, but her classmates have trouble seeing that. Lisa is an 18-year-old white female who considers herself first and foremost to be a conservative Republican. She is concerned about being in a course on “issues” because she feels that the course will have significantly more students who lean left than right and she wonders if she will be pressured. It also makes her uncomfortable that most of her classmates are from large cities while she is from a rural area. What will people think of her accent, her values? And as a first-generation college student, she is even less sure about what to expect. As one can imagine, my empathy map helps me think generally while my composite personas help me remember that I’m not teaching a homogeneous group but a room full of actual people with a wide variety of hopes and fears, strengths and challenges. As I plan, it helps tremendously to keep all these students at the forefront of my thinking so that I explicitly build in the means to ensure that all my students can flourish. If I strictly adhere to the book's sequence for course design, ungrading - a subject that piques a lot of interest - might not come into the conversation for a while. So, allow me to take a quick detour and share some of my personal experiences with ungrading.

I began my journey with ungrading around 18 years ago, although I didn't call it that at the time. Here's what I did: I informed my students that they were starting the course with an A. Should their performance dip below that, I'd notify them and we'd buckle down together to improve it. It was pretty uncommon for anyone to slip under an A, largely because the class projects were designed in a way that permitted multiple revisions. This approach facilitated ample feedback, enabling students to refine their work until it was A-level. This method served me well for a good while. Then for reasons I can't precisely pinpoint or recall, I decided to shake things up. I transitioned to a course rubric-based evaluation system. I graded certain elements, and students self-evaluated on others. Eventually, students would present their arguments for the grade they believed they'd earned. I'd have the last word, but they needed solid evidence to support their claims, so I rarely had to downgrade anyone, although there were instances where I'd challenge their evidence. At such times they would generally admit that they might have overestimated their grades. More often I'd encounter students underestimating the quality of their work. Once, a remarkable student assigned herself a failing grade. It turned into a beautiful dialogue about her self-perception and of course I gave here the A she had clearly earned. It was a teachable moment. Since I teach the same group over three semesters, I had the opportunity to observe her growth. The second semester she gave herself C's which I turned into A's. But by the third semester, she was confidently awarding herself A's. Thrilling. In 2016, I came across Linda B. Nilson's work, Yes, Virginia, There's a Better Way to Grade, and decided to give specifications grading a whirl. To break it down, I devised ten 'challenges' (small to mid-sized projects) per semester, all of which were evaluated on a pass/fail basis. In my world, these translate to 'keep working' and 'you got it'. To earn a 'you got it', students must meet (B-ish) or exceed (A-ish) the specified criteria. This system's beauty lies in its accessibility; even students anxious about the notion of ungrading find it easy to comprehend and adapt to. Hence, I still employ this method, especially in courses for first-year undergraduates or my graduate students' introductory program. I highly recommend it. Of course, the number of challenges is flexible; you can tweak it according to your needs. It's generally beneficial to break larger tasks into smaller sub-tasks, each counting as its own distinct challenge. The course I'm currently designing doesn't quite fit any of these ungrading methods. The subject matter naturally calls for a discussion-oriented class, emphasizing the gradual development of transferable skills like information literacy and critical thinking, particularly in verbal interactions. I've always been intrigued by a standards-based approach to ungrading, so that's the plan I'm leaning towards. But that is a conversation for another day. The Course

I am in the process of creating a new course from scratch. This course, titled "Investigating Critical Contemporary Issues in Education" (also known as "Critical Issues"), is a common offering in colleges of education across the country. It is often one of the first courses a prospective education major would take. While my institution has offered it for as long as I can remember, this will be my first time teaching it. The course will have 25 students and will be taught on campus on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 5:00-7:15. Given how commonly it is taught, I could research how others have approached it, which would be practical. Why reinvent the wheel? Yet, my area of expertise lies in course design, and I'm aware that fresh, innovative ideas often sprout from a clean sheet of paper. Besides, it's not uncommon for faculty to develop entirely new courses, and I want to demonstrate that process. I already plan to structure the course around principles of "ungrading" or minimizing grades, and I aim to incorporate artificial intelligence extensively. Both these factors might necessitate a departure from conventional methods. Above all, I'm eager to see what happens when I follow the steps we outlined in Learning That Matters, much like a novice would. Teach Who You Are In Learning That Matters, one of the first exercises we suggest (pp. 12-15) is contemplating who you are as an educator. I've seen firsthand how educators "teach who they are," and I recognize the same truth in myself. As a philosophy major as an undergrad, you might assume I would favor theory over practice. Yet, I discovered early in my career that a primary focus on theory led teachers and future teachers to seldom incorporate strategies related to those theories into their classrooms. I am all about modeling effective practices and designing authentic tasks that enable my students to apply their knowledge. My students would probably say that I am obsessed with challenging the status quo in teaching. I firmly believe education in the US, while good, could significantly improve. I study schools, systems, and countries that have had the most success in delivering powerful learning to ALL students, including students who have not traditionally benefited. Diversity is one of our nation's greatest strengths; how can we ensure everyone reaches their potential? Although I may not naturally be the most nurturing, I am fervent about applied positive psychology in education. Since earning my certification in early 2020, just before the pandemic, I've been dedicated to improving my students' psychological fitness actively. In my bio, I state that my primary research question is, "How might we re-enchant learning to help faculty and students flourish?" This question truly is my driving focus. Here are three quotes that resonate with my teaching philosophy:

I recognize my shortcomings, particularly in areas where other, perhaps more traditional, educators excel. I understand the importance of spaced retrieval practice. Students need regular review of foundational knowledge through quizzes or equivalent strategies, but this is often the first thing I'll omit when I’m running low on time (which is most of the time). Formative assessment and feedback are crucial for learning and represent one of the most critical aspects of our job. While I do alright in this area, I know I need to do more and do it more explicitly and intentionally. Students need a strong sense of steady progress, but I haven't consistently implemented it. Also, I frequently try to cram in too much content— a poor habit, but I just love it all so much… I am committed to improving this. I acknowledge that my blog will often express views and methods that others may disagree with, sometimes with good reason. That thought unsettles me, but I also realize that we won't achieve our educational goals without making our teaching more transparent. I would define myself as a risk-averse individual who perseveres anyway. Today, I invite you to set aside some time to reflect on your teaching persona. If you have a copy of Learning That Matters, use it to guide you through this introspective exercise.

In a June 2023 Chronicle Newsletter from Beckie Supiano, Robert Talbert "…offered a challenge to the champions of ungrading: 'Take your colleagues behind the scenes and demonstrate how it works. Give us the details,' Talbert wrote. 'Get unapologetically into the weeds through longer-form approaches of communicating your practice.' A good way to do this, Talbert recommended, would be writing a blog." OK, Robert, I accept your challenge, and I want to take it up a notch. What if I chronicle not only my ungrading practice but everything I champion?

So, what do I champion, and what will I report on?

You might be wondering, "Haven’t you always followed all the advice from your book and your workshops?" Well, to some extent, yes. I make it a point never to recommend anything that I haven't personally tried. Yet, I find myself grappling with the challenge of consistently and diligently following my own advice at the highest level. I tend to focus intensively on some aspects of my teaching and neglect others. There have been instances where I've cut corners or initially implemented great ideas only to let them slide as the semester progressed. When you’ve taught and studied teaching intensively for 30 years, you can pull off a pretty good course without going for broke. I’m glad for that, because none of us can go all-out all the time, but what if every once in a while, I did? And what if I invited others to follow my adventures, including all the highs, lows, unforeseen surprises, and inevitable weirdness? In Learning That Matters, we encourage faculty to design transformative courses through specific steps and strategies, but what does it look like when one does that? And since the book was published, I’ve become obsessed with three newer arrivals: ungrading, the Art of Gathering, and artificial intelligence; what happens when I add those to the mix? Robert Talbert reached through my computer and told me to get in the weeds, and into the weeds we shall go! I’m going to invite my students to post to the blog alongside me so you can see what all this looks like through their eyes. Furthermore, I will often include links to examples so that when you want more and deeper weeds, you’ll have that. And I’ll see how my students feel about the possibility of video recording sometimes. If I can, I will. Welcome to "The Year of Teaching Dangerously"! Be a supporter: spread the word, follow us on Facebook @icbgers, and join the list to get an update when I post |

AuthorI am Cynthia Alby and I am a full-time professor specializing in secondary and higher education at Georgia College, but I also write and present extensively on course design. I am co-author of Learning That Matters, and for more than 20 years I have taught faculty from across Georgia in a year-long program on teaching through UGA’s Louise McBee Institute for Higher Education. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed